⇨ Economists say the US is in for a recession in early 2023.

⇨ Lower demand is making for a weak US chemical outlook after a strong 2022.

⇨ US chemical producers enjoy raw material advantages over foreign competitors, but overseas demand might not support exports.

The US chemical industry is headed for a soft patch. Most economists expect a mild recession early this year, which would throw cold water on chemical demand and production. Advantageous raw material prices continue to make the US industry globally competitive, however, and exports should be brisk—provided that offshore demand holds up.

Already, higher prices born of inflation have hit the wallets of US consumers. In response, the Federal Reserve has been combating inflation by raising interest rates, which increases the cost of borrowing for major purchases like houses. Add weakening European and Chinese economies to the mix, and it spells a likely US recession.

“However, the recession is projected to be short and mild, amid a strong labor market and relatively healthy consumer and business balance sheets,” wrote the Conference Board, an economics think tank, in a November report.

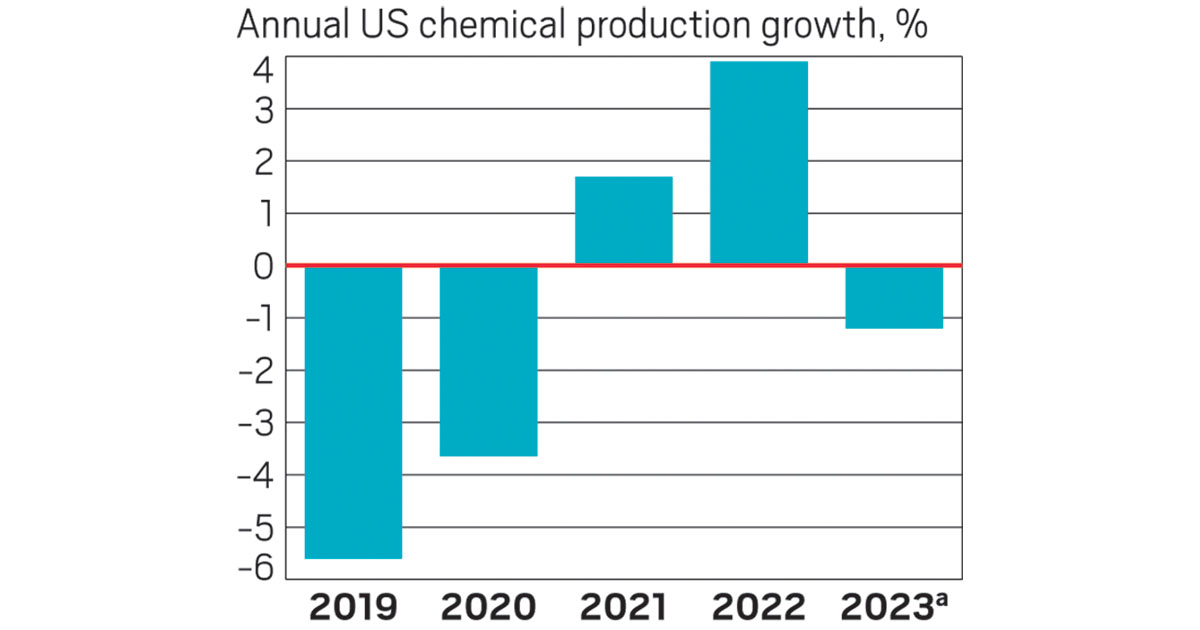

The American Chemistry Council (ACC), an industry group, also expects a shallow recession. After a strong 2022, in which US chemical production rose 3.9%, the ACC forecasts that output will decline by 1.2% in 2023.

One reason, the group says, is that construction of new homes, a big market for the chemical industry, will slip in 2023 because of the high cost of borrowing.

But another big chemical market—automotive manufacturing—could be a bright spot, now that a computer chip shortage that had been weighing on the industry is clearing up. The ACC forecasts that US sales of light vehicles will increase from 13.8 million units in 2022 to 14.9 million this year. “There’s some decent pent-up demand for vehicles in the system right now,” the council’s chief economist, Martha Gilchrist Moore, told reporters in December.

US chemical output is expected to slip this year after a strong 2022.

Source: American Chemistry Council. Note: "Chemical production" excludes pharmaceuticals. a Predicted.

As always, the US chemical industry’s fortunes will depend to a large degree on the global competitiveness of its ethylene and other basic petrochemicals. Ashish Chitalia, head of petrochemicals, polymers, and sustainability management at the consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, says business was good in the first half of 2022. Demand was strong, and a tangled supply chain kept imports out of the market.But toward midyear, he says, demand slowed and the supply chain straightened out. Inventories spiked and petrochemical makers had to reduce operating rates.

The industry will work down this inventory during the year, according to Chitalia. “We are expecting in the second quarter of 2023 we’ll see a balanced situation in North America,” he says.

Relatively low energy prices should be a positive for the US chemical industry in 2023. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shocked energy markets in 2022. Oil prices soared, rising by about 50% through June before falling.

The war’s impact on natural gas prices was even stronger. It was greatest in Europe, which depends on Russia for much of its supply, but the US wasn’t spared. US natural gas prices hit their highest levels in more than a decade as producers redirected liquefied natural gas exports to Europe.

Right now, it costs twice as much to produce ethylene in Asia as it does in the US. Ashish Chitalia, head of petrochemicals, polymers, and sustainability management, Wood MackenzieBut US prices never got so high that natural gas was more expensive than oil on an energy-content basis. This is good news for US chemical producers, which typically extract petrochemical raw materials from natural gas instead of petroleum, as most of the world does.

“Right now, it costs twice as much to produce ethylene in Asia as it does in the US,” Chitalia says.

Michael McMurray, chief financial officer of the petrochemical maker LyondellBasell Industries, told the Citi Basic Materials conference in November that he is watching whether the Chinese market will be robust enough to draw US exports. China imports 40% of the polyethylene it consumes, but the country’s zero-COVID policies have slowed its giant economy.

“We really need China to kind of reopen, I think, for the overall demand environment to improve and hopefully for margins to start improving as well,” McMurray said.

Discussions about how to control plastic pollution will dominate the international environmental policy agenda this year.

⇨ Negotiations on a plastics treaty will be in full swing.

⇨ Governments will consider whether to control groups of related chemicals, rather than just single compounds, under a treaty on persistent organic pollutants.

⇨ Countries will try to revive an expired agreement to improve the global management of commercial chemicals.

Controlling plastic pollution and persistent pollutants and improving the management of commercial substances will top the international policy agenda for chemicals this year.

The first talks on a global agreement to curb plastic pollution ended in December, and negotiators have scheduled second and third rounds of negotiations for later this year. The fourth round and a final, fifth round are set for 2024.

Major issues are whether a future agreement will include restrictions on production of single-use plastics and on toxic chemicals intentionally added to plastics to impart useful characteristics.

Negotiators also haven’t determined whether to embrace chemical recycling techniques being pushed by the plastics industry and the US government. The main commercial form of this technology, pyrolysis, is not available in much of the world, and questions remain about its economic viability.

Also up in the air is the role scientists will play in advising negotiators and partners to the completed agreement.

Bethanie Carney Almroth, a professor of environmental science at the University of Gothenburg, is part of an informal network of about 150 scientists from around the world who are looking to help. They want to provide guidance so that negotiators can craft a science-based agreement and prevent regrettable substitutes for current plastic items, she says.

Some governments are skeptical about this idea. They prefer to rely on international agencies, including the UN Environment Programme, World Health Organization, and Food and Agriculture Organization to provide scientific advice for the talks.

Other countries are suggesting that the plastics agreement establish an official science advisory group to counsel governments on future actions—similar to a panel formed under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. That body reviews scientific data and makes recommendations to treaty partners on which chemicals should be banned or severely restricted.

The chemical industry supports the idea of a scientific advisory group for the plastics pact, says Stewart Harris, speaking on behalf of the International Council of Chemical Associations, an umbrella group of industry organizations. He says the sector wants to ensure that industry scientists, who have deep expertise on plastics, are part of the advisory group.

Meanwhile, governments will gather in Geneva in early May to determine if they will add more chemicals to the Stockholm Convention. They are scheduled to decide whether to ban the once widely used chemicals perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and its salts and perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride, which was used to make PFOS. PFOS is highly persistent and is toxic even at very low concentrations.

They will also decide whether to adopt recommendations from the convention’s Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee to ban the insecticide methoxychlor. And governments are considering controls on the ultraviolet stabilizer UV-328, which is used in many types of plastic.

At the May meeting, governments will consider controlling classes of chemicals rather than individual substances under the Stockholm Convention, according to Bjorn Beeler, international coordinator at the nonprofit International Pollutants Elimination Network. Classes could include UV stabilizers, certain flame retardants, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and chlorinated paraffins. Each of these groups has members with similar toxicity and persistence.

Chemical makers have concerns about a class-based approach to chemicals under this treaty, says American Chemistry Council spokesperson Andrew Fasoli. At times, he says, it is appropriate to list more than one chemical—such as PFOS and its salts. But to legally list broad classes of molecules in the treaty, governments will need to negotiate an amendment, Fasoli adds.

This year, governments will also attempt to revive an agreement to improve the management of chemicals globally. The Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM), established in 2006, is a set of policy guidelines that expired in 2020. Negotiations to extend SAICM through 2030 were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Negotiators will restart work on SAICM at the Fifth International Conference for Chemicals Management in Bonn, Germany, Sept. 25–29. The chemical industry has backed SAICM since its inception as a way to ensure that all actors in the supply chain are trained and accountable for the safe handling of commercial chemicals.

US Environmental Protection Agency administrator Michael S. Regan participated on a panel with (left to right) Beverly L. Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice; Robert Bullard, director of the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice; and Peggy Shepard, executive director of We Act for Environmental Justice at COP27 last year.

⇨ Commitment of federal dollars for environmental justice has reached a record level under the Biden administration.

⇨ Community leaders are mobilizing to ensure federal money reaches communities of need.

⇨ Environmental justice leaders have taken an advisory role at the federal level.

“I think 2023 will be a very busy year,” says Robert Bullard, director of the Bullard Center for Environmental and Climate Justice. “Busy from the standpoint of building on some of the wins that we were able to achieve in 2022, particularly as it relates to getting environmental and climate justice integrated into federal policy, and making sure resources and funding follow those priorities.”

Bullard, Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University, notes that federal funds and programs from President Joe Biden’s administration amount to a level of support that the environmental justice movement has never seen before. The $369 billion Climate Bill, part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, for example, commits $60 billion to establishing grants and funding clean energy and environmental mitigation projects in disadvantaged communities.

More broadly, the Biden administration has committed to channeling 40% of the benefits of relevant federal investment to communities that bear a disproportionate environmental burden—a program called Justice40.

The problem now, Bullard says, is ensuring that the money—especially the federal funding that is distributed through state and local governments—gets to the right places. The prospect of inexperienced community organizations forming to compete for funding with groups that have been working on the front line for years concerns him.

“We are saying that we will not sit idle while we see money siphon off into places and into programs and going to projects that bypass our communities,” Bullard says. “That is the 2023 challenge.”

Peggy Shepard, executive director of We Act for Environmental Justice, says the onus of seeing that promises to communities are kept is on the communities themselves.

“The whole foundation of working to achieve environmental justice is local,” Shepard says. But essential resources are lacking at the local level. “We have some communities with maybe one staff person. You can’t really do a lot if you don’t have staff. If you don’t have a policy person, how are you engaging with the federal government? How do you engage on the state level on climate change?”

Shepard adds that local and state elected officials, and even some members of Congress, are unfamiliar with the Justice40 initiative. Last month, We Act kicked off an 11-city tour intended to bring community leaders and elected officials together to raise awareness of the 40% directive.

Awareness of the broader environmental justice movement has risen, however, beginning with the focus on racial inequality in the US that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and then-candidate Biden’s avowed commitment to environmental justice. Shortly after his inauguration in 2021, the administration announced establishment of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council.

Shepard, cochair of the council, says environmental justice has been given a much more prominent seat at the federal table. “We might have known one or two people at a federal agency, generally the EPA,” she says, referring to the Environmental Protection Agency. “But the council has provided more access and input to other agencies—the Department of Transportation, Department of Energy, Department of the Interior.”

And these agencies require guidance on where resources are needed at the local level, Shepard says. “The issue with the federal government is they are trying to implement something transformational and formative, but they have not created the structure to do that.”

Community advocates also plan to be heard on the international climate policy stage in 2023. We Act, the Bullard Center, and the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice hosted a climate justice pavilion at last year’s UN Climate Change Conference, or COP27, in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt. The pavilion, which in recent years has been located in the general area known as the Green Zone, was for the first time in the Blue Zone, where policy makers and delegations have pavilions.

The groups held several panels, one of which included EPA administrator Michael S. Regan. “We explained the challenge that all our states are not created equal,” Bullard says. “There are some that will do a great job in distributing money in a way that will follow need, and others in a way that will be problematic. And [Regan] said in public that if a state is not spending money in a way that is designed, EPA will withhold the money.”